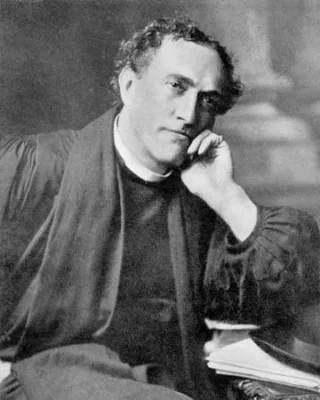

Conrad le Despenser Roden Noel (12 July 1869 – 2 July 1942) was an English priest of the Church of England. Known as the “Red Vicar” of Thaxted, he was a prominent British Christian Socialist.

According to The Friend, “Conrad fought passionately against hypocrisy and oppression, against the Philistine and the Puritan, particularly the Puritan. He sought tranquillity, but it eluded one so militant. His temperament urged him to battle even for the beauty which he so prized in worship, no less than for the Church Socialist League. The story of his life has much charm and contains many echoes of his characteristic laughter.”

Conrad Noel’s private tutor was Herman Joynes, Henry Salt’s brother-in-law. It was during Conrad’s visits to the Joynes home in Brighton that he and Henry Salt became friends. Conrad’s friendship with Salt lasted a lifetime and he was a regular visitor to Salt in his final years.

Introduction

Conrad Noel, the “Red Vicar” of Thaxted, England, was one of the most colorful figures in the Christian Socialist Movement. Along with Percy Dearmer (of The Parson’s Handbook fame) he was a dissident left-winger in the Guild of St. Matthew and the Christian Social Union, “bringing consternation to Stewart Headlam and to Scott Holland respectively,” as Peter d’A. Jones remarks. Noel was one of the founders of the Church Socialist League in 1906, but left it in 1918 to found the Catholic Crusade.

Never modest in its objectives, the “Catholic Crusade of the Servants of the Precious Blood” aimed, among other things:

To create the demand for the Catholic Faith, the whole Catholic Faith, and nothing but the Catholic Faith. To encourage the rising of the people in the might of the Risen Christ and the Saints, mingling Heaven and earth that we may shatter this greedy world to bits.

Noel’s socialism was not of the milk and water variety; he had little use for the gradualism of the Fabians or the opportunism of the British Liberal and Labour Parties. He saw through the hollow promises of post-war “reconstruction” made by the ruling classes to secure the cooperation of labour during the First World War, and warned his congregation:

We must mark the sinister proposals that are being made in high places for such social reconstruction as will inevitably forbid the restoration to the poor of hard-won liberties willingly surrendered during the war. . . Reconstruction without revolution is evil, for Reconstruction must be the outcome of Revolution. In the Battles that will have to be fought against the forces of death, whether frankly reactionary or masquerading as State Socialism and Social Reform, we must ally ourselves with the forces of life, and with St. Ambrose of Milan, with St. Thomas of Canterbury, with Our Lady of the Magnificat. And in the coming rebellion against the Prussians in England, Catholics will need such fiery allies to save them from the tame surrender of Nonconformist and Agnostic labour leaders, and to steel our spirits in these days when ‘whoseover killeth us will think that he doeth God a service.’

And in 1919 he told a Church Socialist League meeting:

Heaven forbid that Trade Unions should trust the leaders they elect, but Heaven forbid that they should continue to elect such leaders! Much better that the rank and file should kick over the traces than follow placemen, gas bags, puritans and lobby worms who misrepresent them, but if the rank and file had been more creative it would have produced leaders it could have followed.

Upon the formation of British Communist Party in 1920, the Catholic Crusade explored possible affiliation with the Third International. As Reg Groves comments, “It was quickly evident that the Third International would have rejected the request; and that if they had accepted it, the relationship would have been a brief one.” Some years later Noel became loosely supportive of the “Left Opposition” grouped around Leon Trotsky. Finding the membership of the Crusade too uncritical of Stalinism, Noel split it to found the Order of the Church Militant, of which F. Hastings Smyth was at one time a member.

Maurice Reckitt writes of Conrad Noel:

It cannot be questioned that in virtue alike of the vigour and fertility of his mind and the force of his personality, Noel was for two full decades the real leader of the political and ideological Left in the Church of England. The ‘Battle of the Flags’ at Thaxted Church in the early ‘twenties, whatever may be thought of the validity of the issues or the wisdom of entering on such a conflict, was the sort of tussle that only such a man as Noel could have inspired and so long sustained.

Like many Socialist-minded clergy whose convictions extinguished any chance for preferment within the Church, he bounced from job to job, lecturing for the Church Socialist League and on many secular Socialist platforms, until offered a position at Thaxted by the patron, the Countess of Warwick. She was an aristocratic socialist and feminist, an admirer and biographer of William Morris, who apparently rather hoped that Noel would simply use Thaxted as a base from which he could continue his speaking engagements around the country. Noel, however, took his responsibilities as Vicar seriously and settled down to make Thaxted parish church a center for liturgical and social renewal which attracted attention from around the world. A passage quoted in Conrad Noel’s autobiography captures some of the spirit of the lively movement he led:

The revolutionary teaching at Thaxted may be studied in books and pamphlets on sale in the church, but the Thaxted experiment is by no means only concerned with the pulpit and the press, but just as much with the life of a group and the expression of that life in worship. Thaxted is becoming a place of pilgrimage for those who are tired of the sluggish routine and conventionalism of much modern Nonconformity and of the ‘C. of E.’ We are proud to claim membership in the Church of England for she is the Church of Anselm, of Becket, of those such as Langton and John Ball who fought for the freedom of the people, the Church of Laud in his fight against a narrow Calvinism and the oppression of the poor, and in still more modern times, the Church of Maurice and Kingsley, of Scott Holland and Stewart Headlam. All this the ‘Church of England’ calls to mind, but the ‘C. of E.’ is only another name for the Establishment, and the Establishment is the religion of the ratepayer, and the religion of the ratepayer is not a religion but a disease.

Now what is there in the Thaxted worship which scandalizes the ‘ratepayer’ and attracts many in the town itself and many pilgrims from all quarters? Perhaps it is the homeliness and unconventionality which many people appreciate. The organ and surpliced choir no longer predominate. The processions on High Days and Holidays include not only the ceremonial group in bright vestments, but the people themselves, children with flowers and branches, women in gay veils, men with torches and banners, all this colour and movement centering round the Lord Christ present in the Eucharist. We preach the Christ Who all through His life stressed the value of the common meal, the bread and wine joyously shared among His people, the Mass as prelude to the New World Order in which all would be justly produced and distributed. The Lord thus chose the human things of everyday life, the useful bread and the genial wine, to be the perpetual vehicles of his presence among us till His kingdom should come on earth as in Heaven. But all this involves politics, and we are often rebuked for mixing politics with religion. Well! the blind following of any political party, the politics of the party hack, these are certainly not the business of the pulpit; but politics, in the wider sense of social justice, are part and parcel of the gospel of Christ and to ignore them is to be false to His teaching. Worship and beauty are not to be despised, but worship divorced from social righteousness is an abomination to God.

Conrad Noel, An Autobiography, edited with a foreword by Sidney Dark. London, J.M. Dent, 1945.