One of the great disadvantages of the dress and tenue of the present generation is that, so far as men go, everyone tends to look more or less like everyone else. There are few sharp and decisive demarcations of attire and deportment, which used, when I was a boy, to divide men conveniently into generations, so that at a glance they could be unhesitatingly referred to a particular stratum and era of life. Nowadays, if a man’s hair does not turn white or disappear altogether, if time does not “delve the parallels on beauty’s brow,” it is not always easy to tell a Professor from an undergraduate, though perhaps the undergraduate would not cordially endorse the statement.

When I went as a small boy to Eton it was very different. It is true that the elder boys, with their sausage-shaped whiskers, would now be regarded by an undergraduate as clearly belonging to the ancientry. But no one could have confused them with the older masters, whose age, to judge by their appearance, one felt could hardly be assessed in Arabic numerals, but would require algebraical symbols or logarithms.

They wore then, if it can be believed, great hats of a peculiar tallness, rich in substance rather than glossy; high, crumpled, cheek-scraping Gladstone collars, the danger of which seemed to be that a sudden movement might cause the collar point to pierce the eyeball—but then no sudden movements were made by such as these! A big white tie, negligently tied, in the shape of the sails of a windmill; a soft pleated shirt-front, a frock-coat often of black broadcloth, dark trousers, which looked in their uncompromising creases as though they were made of painted metal, the legs having a marked tendency to assume a corkscrew shape, and boots of great size and rigidity, resembling small boats ;— far-off their coming shone !

This is no exaggeration; among the Fellows and senior masters there were several such figures. They moved stiffly, like men encased in armour, they spoke gruffly, they dissembled both Christian graces and virtues; the one emotion they inspired was awe; yet if you came by any chance to know them, they turned out to be mild, kindly, reasonable people, not in the least corresponding to their panoply and countenance.

The next generation of masters had a touch of modernity about them. Their collars were less obtrusive, their ties had the semblance of a bow. They wore morning coats and their movements were less hampered. But in one respect they were distinguished from their younger colleagues. They shaved only the upper lip, a fashion which has a curiously distorting effect upon the human mouth, making it appear like an orifice into which something requires to be slipped or posted. It was a fashion, I believe, originally invented by Cardinal Bellarmine, but it was one of those deleterious arrangements which one can conceive of as having been invented; the only inconceivable thing is that it should ever have been repeated.

Yet in the early seventies such figures walked the streets of Eton and aroused neither astonishment nor terror They preached, taught, conversed like other men, though they never seemed to take active physical exercise.

One of these figures, but with the marked difference of an extreme juvenility of motion, was the Rev. James Leigh Joynes, formerly known as “Jimmy,” but on whom later generations of Etonians had conferred the supreme brevet of affection and respect, the simple title of “Old.” To be called “Old” by everyone at a comparatively early age is an honour only to be earned by unfailing kindness.

He was born in 1824, one of five active and able men, sons of the Rector of Gravesend. He was just fifty when I went to Eton. He had been a boy there, and had won almost every schoolboy honour. He played for five successive years in “Collegers and Oppidans,” he was by far the best fives player in the school. He was “sent up ” for good no less than forty-six times, he was President of Pop, Newcastle Scholar, Captain of the School. He was modest, kindly, and universally popular ; and he was gratefully remembered by his schoolfellows for the fact that he set his face firmly and courageously against all bullying and oppression, all improper talk and undesirable habits. This was resented by some, but resented in silence, for slander, malice, and ridicule were alike genially ignored by Joynes.

He went to King’s as a Scholar, won a University prize or two, and returned to Eton as a master and a Fellow of King’s in 1849.

He was a very successful housemaster (at Keate House) and tutor. Many of his pupils—among whom were Sidney Herbert (14th Earl of Pembroke), Swinburne, Lord Kinnaird, and the late Duke of Argyll—rose to high eminence. He played fives for many years with the boys, and his pair were very rarely beaten.

As a teacher he was an admirable disciplinarian; he seldom or never set a punishment; he had the gift of very ironical and caustic speech, delivered with extreme fatherliness, in a tone of grave concern and evangelical piety. I have been told a story by an eyewitness of the way in which he handled a loutish, thoroughly ill-conditioned boy, whom I will tactfully call Abbot, who began by making himself deliberately offensive. Old Joynes brought up his batteries with smiling unconcern. He never lost his temper, but he watched his opportunity. Abbot brought paper into school, and holding it under the desk, proceeded to write a punishment for another master. “Abbot, Abbot,” said Joynes admiringly, “what can you be doing? Look at Abbot, boys. There he sits, inditing a sonnet perhaps to his lady’s eyebrow. Ah, he’s a fortunate fellow, Abbot—‘Di tibi divitias dederunt et Di tibi formam.’” By this time everyone was giggling, and Abbot made a sulky rejoinder. “Abbot, we don’t talk like that here! Come, take your book, and stand in the corner, there’s a good boy!” The wretched Abbot, seeing that the fates were against him and hoping to propitiate his castigator, heavily obeyed. But old Joynes had not finished his basting. Abbot stood with his back to the room. “Now, boys,” said Joynes, “look at Abbot; what a good boy he is! How obedient! Many boys, if I had told them, to stand in the corner, would have said he ‘Joynes, Joynes, who’s Joynes?’ But Abbot takes his book and stands in the corner, as good as gold.” It was simple enough, but entirely effective. There was nothing tyrannical or resentful about it. Abbot on coming to his senses was left in peace, and nobody felt inclined to try further a fall with Joynes.

As for his teaching, it was sound, old-fashioned Eton scholarship, which was a curious little exotic bloom of culture, conventional and narrow, and based upon a minute acquaintance with two or three authors. There was no great width of erudition in it, nor did it exactly stimulate thought; but it consisted in a very nice appreciation of certain literary values, arrived at by a constant comparison of passages: and here lay its virtue, that it was arrived at, and not crammed in. The old Eton scholars knew Horace by heart, and there was endless quotation and illustration, both of words and phrases. It was not scientific, and the grammar was fanciful, but the method was good. It did not develop originality, because the ideal of composition that was held up was not to use Latin in a Horatian way, but to work in Horatian tags into a very delicate piece of mosaic. But the effect of it on an original mind, like that of William Cory, was that it enabled him to produce a book like Lucretilis, which Munro said was the most Horatian thing ever written since Horace, and which owes its unique and delicate charm to the fact that one finds in it real poetry, full of exquisite feeling and pictorial description, yet all run into a Horatian mould. Joynes was a hardworking and conscientious man, but tough and wiry as he was, he had a touch of valetudinarianism about him, felt the strain of his work, and disliked responsibility, though he never shirked it.

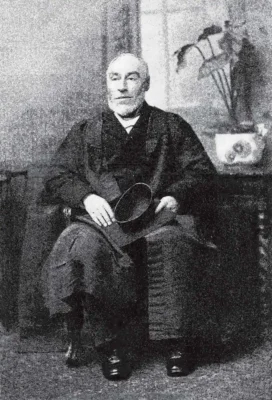

There is a well-known caricature in Vanity Fair of Joynes standing in cap and gown, brandishing a birch and pointing with an air at once sinister and pastoral to the flogging-block: he at least was prepared to do his part! The half-closed eyes, with their dull shadows, the big devouring mouth, give the picture a grim quality. I believe that if as a small boy before I went to school I had been shown the picture, it would have terrified me profoundly, and even mingled with my dreams; indeed at best there is something ugly, some touch of primitive horror about it. It was like the original in a sense, but only in one, and that a rare mood. But the truth is that the appearance of Joynes was very singular. He was short and broad and very strongly built, his small and sturdy legs slightly bowed outwards. He looked and was extremely active ; he ran rather than walked, his big feet twinkling along, and rounded corners at a great pace with a suggestion of a caper.

He had a large head with marked features which, in combination with his short stature, gave him a somewhat gnome-like aspect, a large aquiline nose, stiff, wiry, upstanding hair, grizzled and cut short, and a short “Newgate fringe,” with shaven lips. His complexion was pale and dull, his eyes somewhat sunken; his mouth wide and large, and full of big white teeth, the indenting lines from the nose to the ends of the mouth very marked. But there was never a face which showed such marked alternations of expression. The general expression of his face was grave even to melancholy, and preoccupied, one would have said, with sad thoughts. But he had a very quick and irradiating smile when his mouth opened up along all its lines, accompanied with a rapid upward jerk of his eyebrows. His face was never still for a moment when he talked, but twitched and darted curiously; and he had a sudden, loud, almost harsh laugh, almost frighteningly boisterous, and full of goodnature, which he delivered pleno ore, so that one saw displayed his big white teeth, and which ceased as instantaneously as it had begun. It was a very impressive face in repose, mournful, weary, brooding; and this gave it an almost dramatic quality as he talked, because of its lively motions.

He was very kind and fatherly in manner, recognising one and repeating one’s name in a comfortable and welcoming way. His voice was strong and pitched rather low, with a serious accent; the tone full of goodwill and geniality as he talked, but in general talk it often sounded as though he were uttering private reflections aloud rather than conversing. He had a marked pronunciation, clipping some words rather short, prolonging and broadening vowels; altogether an unusual figure, at first sight disconcerting and even alarming, but with a paternal geniality showing through.

It was in 1877 that one of the Fellows died, and Francis Durnford, the Lower Master, became a Fellow. Joynes succeeded him as Lower Master, and I well remember how we saw the then Captain of the School, going off carrying a birch tied up with blue ribbons, which according to custom was always formally presented to a new Lower Master.

It was an immense surprise to me when I first heard Joynes preach in chapel. I had expected something commonplace, possibly even absurd. He trotted, a little nervously, to the pulpit behind the verger, in a full surplice, broad black scarf, ample hood. To my surprise, he gave out his text in a grave and resonant voice, and launched into a discourse, admirably phrased, serious and tender, with a moving appeal to walk unflinchingly in the path of humble duty and simple goodness; it was deeply impressive; it came unaffectedly from the depths of his heart, and its earnest piety and fatherly affection were unmistakable. We were accustomed, I must add, to very different sermons. Hornby was a clear and impressive preacher, but his sermons were pitched, both intellectually, and morally, almost too high. The old Fellows of Eton, who occupied the pulpit as a rule, were lengthy, tedious, entirely uninspiring. But Joynes delivered a personal message, within the comprehension of all his hearers. A later sermon, on Trinity Sunday, afterwards printed, was really a fine piece of majestic eloquence, and treated the symbolism of the doctrine in a high poetical vein.

But the scene of Joynes’s ministrations was generally the Lower Chapel; and I think it is worth recording carefully what bind of a place in the early eighties was considered fit for small boys, many of them, no doubt, with seemly traditions of home churchgoing, to worship in. The room was opposite the racquet courts, and had been built originally out of the cheapest yellow brick for a musical practice-room. It had a wooden roof, supporting purple slates, and tied together by iron rods. The walls were of thin brick, lightly washed with a kind of buff tempera, the lower part only being plastered. The boys sate in mean stained deal pews, closely packed together. There was a shallow alcove at the east, adorned by a hideous faded hanging of a sort of reddish-brown gimp, of what was called an ecclesiastical pattern of fleurs-de-lys in lozenges. The altar was shabbily draped in a coarse red stuff. An old and wheezy organ in a deal case, with grey metal pipes, stood in one corner ; opposite this was a sort of enclosure, like a loose-box in a stable, which was the reading-desk The grim and dirty place was cold in winter and hot in summer, and from end to end there was not a single feature or object on which the eye could rest without disgust and aversion.

The boys did not behave badly, but resignedly, and treated the performance as a tedious drill. Two high raised desks of stained deal rose above the throng of heads for the presiding masters.

We must imagine, on an ordinary morning—for there were daily services here, as well as two on Sundays—the boys assembled for service, the last belated stragglers hurrying to their places. The door of the so-called vestry, a lean-to shed, creaks. A small procession of a dozen choir-boys from the town, probationers for the Upper Chapel choir, ill-behaved and at constant feud with the Eton boys, issues out, and goes quickly up the gangway. Behind these follows the chaplain, one of the masters, and at the end, Joynes himself.

He never walked in the centre, but shifted about in a curious way—he always found it difficult to walk slowly—first on one side of the gangway, then on the other. He was always afraid in those latter years of catching cold, and the word “draughty” pronounced with a curious flattening of the first syllable, was m his mouth a word of fear. His grizzled hair stuck up stiffly on his forehead, and he used to dart quick, apprehensive glances upwards at the large bare windows, for fear that some ill-advised person had opened a crack to let in air. For the better protection of his own person, he held up one of his surplice sleeves against the right side of his face, and with his left hand he held his cap over the other side of his head, about an inch or two above his hair, to combine reverence and security. He and the chaplain then entered the loose-box, and the service began.

It was the strongest testimony to Joynes’s earnestness that he somehow managed to make something beautiful and impressive out of a service held in such surroundings. His kindly glances, the grave and tender tones of his voice, had an unfailing charm; and his sermons were beautiful, though in later years he repeated himself and depended for interest too much on anecdotes snipped from the daily papers. But it was never perfunctorily done; and because it all evidently meant something serious to himself, the boys felt that it was not wholly in vain. It must be said that Warre from the moment that he became Headmaster considered this infamous building a blot on the place, and the present beautiful Lower Chapel, with its stained-glass and fine carved work, is a marvellous contrast to a slatternliness which even forty years ago was treated as a matter of course.

It was traditionally held that when Dr. Bafeton resigned the Headmastership in 1868, Joynes was sounded as to his willingness to accept the post, and declined it in a kind of panic of humility. He would have made probably a just and firm ruler; but no man was a higher Tory in educational matters. He had no theories on the subject of education, no programmes, and knew and cared nothing for what was going on in the educational world and indeed in the world at all. His motto would have been “Stare super antiquas vias.” He was lost, I believe, in a vague dream of insecure health and personal piety. I have seldom known an able man with a looser grasp of affairs generally. In talking to him you would have imagined that he never read the papers, except in the search for improving anecdotes. He had no political opinions and knew nothing of literature. He asked a young master once where he was going for his holidays. The reply was, “Rome.” Joynes, after a moment of melancholy reverie, shook his head and said, “I shouldn’t like that! I should be afraid of the banditti! ”Swinburne was an inmate of Joynes’s house, but when I attempted to extract from him some reminiscences of the poet, he seemed to be able to recollect nothing, after some cogitation, except that Swinburne had had red hair. When I mentioned his poetry, he changed the subject decisively, with obvious disapproval. The fact was that he lived the quietest of lives in a quiet and affectionate family circle, and subsisted on local news and a slender stock of old stories. But he had a deep vein of real piety. He had a Sunday Bible-class for men-servants, did a good deal of visiting among the poor, and used to read the Bible, with simple exposition, to bedridden and aged pensioners.

He seldom expressed an opinion at a meeting. He disliked all changes in the curriculum, but used to add that so many masters whom he greatly respected had expressed themselves in favour of reform, that he would not press his opinion. French he thought immoral, and science heading straight for atheism.

He married somewhat late in life, his wife being a woman of great sympathy, intelligence, and charm, but so modest and retiring that she took little part in the social life of Eton, though she had many attached and devoted friends. His eldest son was for a time a master at Eton, but he adopted somewhat extreme socialistic and vegetarian views, and was actually arrested as a political agitator in Ireland in the late seventies, where he had gone as a propagandist on a self-sought mission. He was a writer of considerable force and charm, but died prematurely. Another of his sons was a Scholar of King’s and Bell Scholar, and adopted a leisurely life with literary proclivities.

One of the characteristic qualities of Old Joynes, in ordinary life, was his determined mirthfulness. It was a matter of duty to him to bear himself with invariable cheerfulness in all companies. He was fond of little confidential jests, which he would deliver privately into one’s ear, with a hand upon one’s arm or a gentle nudge, survey one’s face to watch the effect of his words, and utter a subdued fragment of one of his hearty laughs. He very much disliked hearing any slander or malicious comment, and always followed it up by expressions of his regard for and confidence in the person concerned. He could administer too a grave and direct rebuke. I remember in my early days at Eton, when I had no doubt rather sacrificed the daily grammar-grind for a more lively and discursive sort of instruction to the fourth-form boys I was engaged in teaching, their performance in the School Trials left, much to be desired. Joynes, then my immediate superior, sent for me. I found him in his study, seated on a high stool at a desk, doing nothing in particular, with a row of medicine bottles within easy reach. He greeted me pleasantly, showed me the list, made me a little compliment on my pleasant relations with the boys, and then said very gravely and impressively that these must not be won at the cost of strict and definite teaching. It was so kindly and yet so earnestly delivered, that it did me a great deal of good, and I never made that particular mistake again.

But in spite of this almost roguish cheerfulness of demeanour, I do not think that Joynes had any deep sense of humour. Indeed he was generally rather shocked by it. At an audit dinner at Eton, at which Canon Keate, the son of the famous Headmaster, was present, the talk turned on longevity, and Canon Keate told a story about the famous “Old Parr,” the centenarian. Joynes’s face fell, and he took on an appearance of pain and concern. However, the conversation proceeded, and presently Joynes brightened up, and excused himself for his temporary gloom by saying with an air of great relief to Canon Keate, “ I thought you were speaking of your father.” That Canon Keate, the most loyal of sons, should have told in public an absurd story about his father, designating him as “Old Pa,” was inexpressibly ludicrous and preposterous to all but Joynes.

But in any case the old man achieved the distinction of being at all events a great figure at Eton, with definite and salient characteristics, and with an atmosphere of his own which differed strangely both in quality and force from the prevailing atmosphere of Eton, and made no concessions to it. He was almost grotesque in some superficial ways, but he was not in the least like anyone else. The essence of such a distinction is probably a simple and preoccupied unconsciousness of observation; but the fact remains that the memory lingers half in amusement and half in tenderness over the remembered glimpses of the man; one can see his face and hear the tones of his voice. He served his generation as he best could. I should not account him a great schoolmaster, or even a notable man, but his was a strong and sincere individuality, and he played a distinct and unforgettable part in the Eton life of his time. With all his queernesses and quaintnesses, there was a conspicuous element of moral beauty about his character; a simplicity, a seriousness, a devotion to spiritual aims, which remains, when all is said and done, as the distinguishing feature of the man.